2 Live Crew live right on the edge, where things can get uncomfortable.

Your money's no good here Mr. Torrance.

David Lynch’s freaky 1986 film Blue Velvet exposed and probed the hidden darkness lurking behind everyday American life. The whole film was off-kilter, inducing a vertiginous nausea and vague terror which coalesced in the psychopathic sadist Frank Booth, played intensely (how else?) by Dennis Hopper. Frank is up to some seriously freaky shit, in particular huffing deeply on this mysterious canister he keeps with him at all times. Nobody had ever seen anything like this, and it was terrifying, despite knowing nothing about this drug that makes you crazy by inhaling it from a tank. It was supposed to be helium, which gives the user a baby voice. Lynch and Hopper together decided that a funny baby-voiced Frank wasn’t really right so he made an actor’s choice and changed it to Amyl Nitrate for dramatic reasons. While “poppers” might make one act in just that way, they don’t come in a tank and you don’t suck on them like Hopper hit that mask. It didn’t matter that it wasn’t a real drug: Frank’s manic inhalations alternating with lunatic commands to a cowering prisoner were the very embodiment of 80’s terror. So keep this scene in mind, that weird life-out-of balance feeling, and read on.

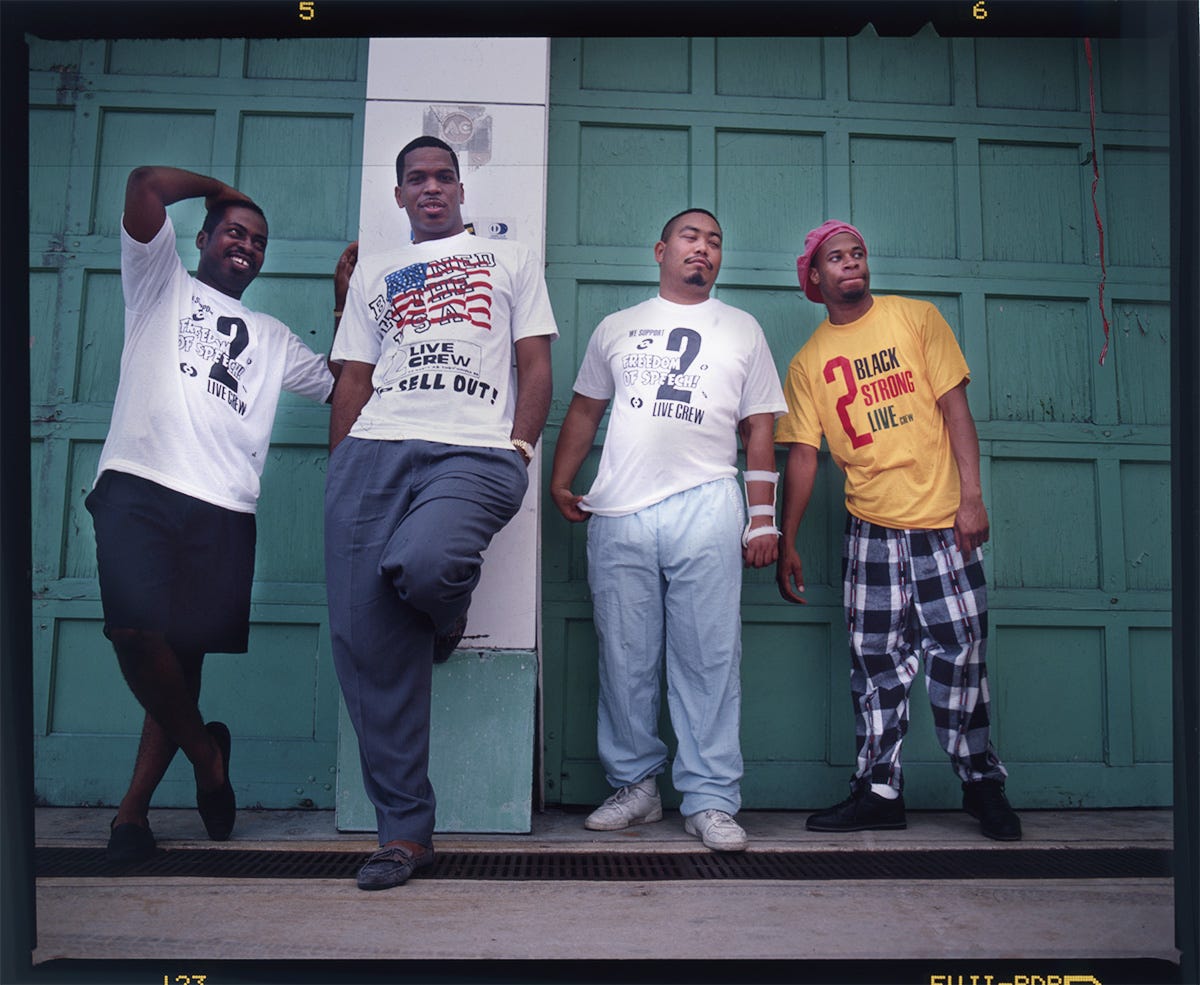

When Jodi Peckman called to tell me to pack for Florida to photograph suddenly-infamous 2 Live Crew, my ears pricked right up. I could hear the excitement in her voice; it was clear she saw this as a bigger deal than just another shoot. The band had just had their (admittedly nasty) album declared obscene by a court, and some poor schlub record-store clerk had just been arrested for selling it to a 14-year-old. The publicity surrounding this was huge, and my editor Peckman was convinced this would be a cover. I had shot three SPIN covers while I worked there, but had never even shot a feature for the mack daddy of clients, Rolling Stone. When I heard I might get a chance to shoot a cover, every hair on the back of my neck stood up and stayed there. Spoiler alert, never did get to shoot a cover for RS, neither that day nor any other. There was a definite hierarchy and sense of leveling-up even to shoot features for RS; covers were a carefully choreographed dance of publicists, artists, agents, publishers and anyone else who might need to be involved. Not my beat, despite my history of creating compelling covers for many other magazines. Even though my pictures appeared in Rolling Stone nearly every issue during that period, for me to be allowed to attempt to shoot a cover was a one-time confluence of newsworthiness, serendipity and wishful thinking.

We were to shoot in 2 Live Crew’s compound “outside of Miami,” which meant we could fly into Miami to get there but it seemed awfully far out into Alligator Alley to me. Said compound was a razor-wire-surrounded concrete lot and a couple low cinder block buildings: cars on blocks, people hanging about nonchalantly pretending not to care while looking you up and down hungrily.

Of course, a young rock photographer would kill to get his photographs on the cover of a national (and legendary) magazine and any band would too. Ah, but 2 Live Crew was not any band. The main guy, one Luther “Luke Skyywalker” Campbell, wasn’t even a performer. He was the main conceptualist and presented himself as the front man. He was riding that censorship stallion like a jockey, manipulating and controlling the media while using publicity to promote their album. Luke would have been fine with a Rolling Stone cover, sure, why not? But as we were shooting, it began to dawn on me that these dudes were crazy, armed, probably on drugs, and really didn’t care at all about being on the cover, or really even involved with Rolling Stone.

That’s where the Hopper thing comes in. When he was huffing on that mask and acting so unhinged, it didn’t matter that that action was an actor thing that wasn’t even real. It was scary as hell watching someone slip their icy fingers underneath the mask of comity and cooperation we all affect, only to reveal a hideous monster. Frank Booth didn’t care how it appeared, he was fixated on that tank and the depravity it enabled. That afternoon with 2 Live Crew reminded me of nothing less than those scenes in Blue Velvet. Everything looked normal, but was shifted in a fundamental and terrifying way.

While frantically shooting to get my cover I had a glimpse of the bad shit going down in that compound, and the lack of shared conceptual agreement on just what was “OK” and what was off limits. I got the feeling Campbell would be just as happy with a couple dead photographers as the cover of Rolling Stone. Doing this gig for all these years, I believed that shooting for Rolling Stone was like a kind of currency that acted like some kind of protective shield around me, allowing me to step willy-nilly into any scene that I knew nothing about. This wasn’t the case “outside Miami.” Your money is no good here, Mr. Torrance. Campbell himself was fine, it was the people and scene around him that seemed terrifying in just the way Dennis Hopper’s Frank huffing on that can while harassing Isabella Rossellini was scary as all get out. We saw the guns, and there was some kind of drug use going on but it was not the pot, cocaine or mushrooms I was familiar with. No, it was some freaky-ass thing that felt like Dennis Hopper had made it up.

When we left the shoot that day my assistant Patty and I met eyes and breathed an actual sigh of relief. I wasn’t the only one to feel intimidated; Patty later told me she’d never been so scared on a job. It was the oddest of vibes on that shoot. Something was seriously out of whack in that compound that day. Was it me? Or was it the combination of Florida, guns, drugs, and alligators?

After that unexpected and rather searing experience I thought fairly hard on it. The pictures are fine, good even. A Rolling Stone cover maybe not, but I certainly felt like I’d made my client happy. But there was that disconnect, that odd feeling of things out of balance, like the Upside Down or Backrooms liminal spaces. It wasn’t so much that we might have been threatened, it was that the shared social compact might not be held in such high esteem by all. And some participants take the theatrical gangster stylings of rap culture and try to bring them to life. I’m sorry I didn’t get that cover, and thrilled to have escaped unharmed and been granted an opportunity to find some new perspective and empathy without needing to visit the ER. Still not really a fan of Florida compounds, but feel like any day the ‘gators go hungry is a good visit.